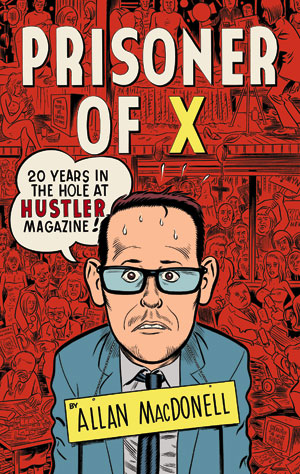

Fayner Posts: Here’s another chapter from former Hustler editor Allan MacDonell’s book. The chapter is titled "Fired."

MOST PEOPLE DON’T have the luxury of reliving their own suicide,

but anytime I want, I can power up my VCR and witness myself

standing in front of 500 gamblers and a few co-workers, all of whom

have gathered to laugh at me as I commit career hara-kiri.

Look at that stooped, thin man stepping up to the microphone. He

stands within the crowded confines of a hotel ballroom. Waiters clear

away dessert plates from a grid of banquet tables, and the guests face

forward, skeptically waiting to be amused. A sign affixed to the front

of the podium reads, “LARRY FLYNT’S X-RATED ROAST.” Hustler

magazine publisher Larry Flynt sits to the right on the rostrum, silksuited

and egg-shaped, inert but imposing in a gleaming gold

wheelchair. Crippled by a would-be killer with a deer rifle 25 years earlier,

America’s cuddliest pariah looks like Humpty Dumpty put back

together again, but older, fatter and dyspeptic. Flynt’s glazed emerald

eyes stare the camera down. His lips hold a pout of gassy forbearance.

The thin man standing to Flynt’s left peers out through thick, blackframed

glasses, scanning the audience of half a thousand as though

it were packed with assassins. The condemned man coughs nervously,

not quite prepared to speak. That man was me.

I leaned sideways and squatted level with the jowly, dispassionate

face of my boss.

“Hey, Larry,” I said, “did you lose a bet? Why are you submitting

to this roast?”

He ignored my questions, as usual. His smile might have been

enigmatic, or maybe it was just a sneer. “I hope you like your job,”

he drawled.

Ambivalence plagued me on that point, but now was not the

time to discuss it. “You know what I do for a living. I write ‘Asshole

of the Month.’ Why pick me for a roaster?”

“You get paid to fuck with people, and I pay you to fuck with

people, but I don’t pay you to fuck with me.”

His mouth clammed shut, his way of saying that no further discussion

would be brooked. I stood up half-straight and faced the

cameras, the crowd and my future.

“My name is Allan MacDonell, and I have come here tonight to

help honor a man who is bigger than life. Wait a minute; I fucked

up already. To honor a man whose head is bigger than life.”

Polite laughter. The audience was thick with milling gamblers

and their mercenary girlfriends, still grumbling about the price of

drinks at the no-host bar. Sitting at the head of this surly mob,

oblivious to the complaints about his cheapness, Flynt puffed up

like a venomous, red-faced toad. When I was a kid, before we’d ever

met, Larry Flynt had been one of my favorite famous Americans.

Discounting the bit about being stuck forever in a wheelchair, it

was fun to romanticize Larry’s reputation as an iconoclast and a

rebel, to envy his profligate wealth and his excesses with the

ladies. Then I’d gone to work for the real guy, and now this:

trapped in a Holiday Inn side room packed full of extras from Marriedto the Mob.

Tomorrow morning, play would commence on a million-dollar

grand slam of poker, sponsored by the Hustler Casino, a hillbillyfabulous

card club owned by Flynt and located in a crummy Los

Angeles suburb. The seven-figure jackpot had drawn hundreds of

high-stakes cardsharps from all over the country. As a treat to the

contestants, the casino’s management was hosting a pre-tournament

dinner. This roast of Larry Flynt followed dessert. Former

President Bill Clinton’s half-brother Roger and former professional

comedian Gabe Kaplan had been recruited to poke fun at the wheelchair-

bound sleaze merchant. A decent roast requires more than

one past-prime yukster and a sibling liability, but Larry Flynt had

been reluctant to shell out for extras. He padded the lineup with

unpaid employees, including me. Who am I? Up until that night, I

was Larry’s trusted editorial director.

I had a dilemma. Larry Flynt is a funny guy. He can take a joke,

up to a point. He is also profoundly sensitive and once offended

tends to stay that way. He resents anyone overstepping their familiarity

with him, but he also punishes timidity. If I cobbled together

a string of anecdotes that went soft on him, he would label me a

chickenshit, and that evaluation would go into the continually

revised mental file he keeps on everyone who works for him.

A few old-timers were lurking around the office, deep-fried charity

cases who’d been leeching off Larry since the 1970s when he ran

Hustler out of a seedy storefront in Columbus, Ohio, and could still

walk. The bolder of these weasels were after my top-dog job, and

had been ever since I’d clawed my way to it years earlier. Undermining

sneaks were constantly sending Larry secret memos

pointing out my imagined failings, memos that Larry would forward

to me. Any passages that he deemed pertinent were double-underlined.

Our sales had been skidding. The entire “men’s sophisticate”

niche of the magazine market was spinning into the toilet. I could

not afford to be notched down in Larry’s timidity category.

On the other hand, if I pressed too close to home with wellaimed

jokes that twisted the dessert fork in any of Larry’s delicate

areas, he might decide he hated me. I’d seen him suddenly hate

better, smarter men than me, men more indispensable to the wellbeing

of his empire, and he’d cast them out as if they had given

him the clap. My commentary would have to talk a fine line, and

there was no way of knowing where that line might be drawn. It’s

not as if I could ask Flynt for ground rules. The man has a sadistic

streak. Nothing would make Larry Flynt happier than to watch

his editorial director—a snot-nosed middle-aged would-be big shot

who thought he was smarter than everyone else—stutter and falter

and slowly die in front of an auditorium packed with poker-faced

friends.

I have a tendency to rush when I speak, slurring words in a

rapid-fire, marble-mouth mumble. I cautioned myself to read my

prepared script slowly, one word for every three beats of my heart.

“A major Hollywood movie and countless TV shows have tried

to get at the real Larry Flynt, the man behind the image. The

movie and TV shows are fine, as far as they go, but if you really

want to take a man’s measure, you should talk to someone who

works for him.”

Even now, many months afterward, I have trouble watching the

videotape. On the screen, I see a lone, thin man sag slightly within

a light trained upon the lectern. The glare off his wet forehead flashes

in the camera lens. He looks toward his right. Larry Flynt sits

within arm’s reach, glowering with impatience.

“I’ve been on Larry Flynt’s payroll for 20 years. And I have the

four-figure net worth to prove it.”

Light snickering gave me confidence that my enunciation was

passable. I shot the cuffs on my Prada suit.

“So I might not qualify for a loan to buy a condo in La Puente, but

I am qualified to give a fair and unbiased account of Larry Flynt.”

A miracle happened. Laughter came, real laughter, loud and

sustained. I was able to pause and gather my wits, waiting for the

outburst to subside. My wife, Theresa, covered her mouth and quietly

laughed, sitting one table away from where Liz Flynt, Larry’s

wife, held court. Liz Flynt waved to me. I looked away so as not to

be blinded by the flash of diamonds on her fingers and wrist.

“Larry called me into his office this afternoon. Between the door

of his office and his desk is about 70 yards of green carpet, the

exact color of money. As I walked across this no man’s land, Larry

glared out at me with pure malevolence, which is how he shows

affection to an employee. His evil face made me think of the man in

the moon squatting on the toilet, straining to force out a dry turd.”

This punch line received less enthusiasm than I had hoped for.

The top of Larry’s head moved at the periphery of my vision. He stifled

a yawn.

“I was afraid that he’d been sitting on one of his testicles all day.

Either that, or Doug the bodyguard had misplaced Larry’s pocket

pussy.”

Again, I was allowed to wait while the laughter died down. It

didn’t take long. My mind concentrated on the task at hand, shutting

out all observational data regarding Liz Flynt and refusing to

consider the potential reactions of Larry to my immediate right.

“‘Allan,’ Larry said, ‘you say whatever you want about me

tonight. It’s a free country.’”

For some reason, the crowd found that funny. Puzzled, but

pleased, I went on.

“Then he had Doug take me up to the roof of the Flynt Building

and show me the view from what he calls the Launching Pad.”

I had them. Poker might be their business, but they were suckers

for my sly, mordant wit. I stuck with the material I had spent

three weekends working on. My jokes shocked me. How could I be so

vile, crass and humorless? I’d unconsciously tapped into a raging

undercurrent of resentment toward my employer. He’d stiffed me on

my annual raise—again—after saddling me with unpaid special projects,

then he had the gall to shove me into this false position.

“I hope it is safe for me to say that Larry Flynt is a complex man,

and working for him is full of contradictions. Larry Flynt runs the

only company in the world where he makes you pay to park in his

building, but he promises all employees a free defense attorney with

every sexual harassment suit.”

That one sank with only slight ripples of amusement, which

didn’t stop me from mining the vein.

“Most of you here, I’m told, know Larry from the gaming world.

He claims he is a world-class poker player. Nobody who works for

him can understand how that’s possible. We can’t imagine him giving

anyone a credible raise.”

The casino crowd fell for the gaming reference, loud and hearty.

This performing was like being an unwilling passenger on a runaway

roller coaster: a sensible person might reason he should

disembark before the first big dip, but knows there is no profit in

jumping off.

“A few years ago, I was at Circuit City with my wife, and we were

spending my Christmas bonus. The wife and I couldn’t decide if we

should buy a toaster or put a Walkman on layaway. I saw a bank of

television sets, and I wondered if I would ever be able to afford one.

Suddenly, Larry’s man-in-the-moon face appeared on a whole row

of TVs. He was on Entertainment Tonight, live from Las Vegas. He’d

just lost a million dollars in one sitting at blackjack. My wife was

shaken by this news. She said, ‘Allan, what if that man loses Hustler

magazine in a poker game, and you’re forced to go work for

some cheap bastard?’”

There is no accounting for what people think is funny. My wife

had predicted this jab would fall flat, but hilarity tore through the

crowd. I put a hand to my sliding glasses and pushed them back up

my greasy nose. I looked up toward the ceiling as if for help. Bigger

laugh. Larry Flynt glowers like an alpha toad who has ingested a

lesser amphibian, one that is too wiry to swallow. The skinny toad

is dead, but still kicking.

“Larry assured me he would never wager something so precious

as his beloved Hustler magazine. He apologized that my retirement

account was another matter altogether.

“And so when I look out at this crowd, I don’t see friends and

associates of my boss. I see a roomful of fuckers who are hoping to

win my 401K money.”

I earned an ovation. Had I stopped at this high point, everything that

had come before might have been forgiven, but the ride was not over.

“There is a common belief that having Larry Flynt in charge of a

porno magazine is like leaving a priest in charge of an orphanage.”

A couple of groans. I was confident that I would win them over.

“Part of my job at Hustler magazine is to review photo sets with

Larry. We take our special magnifying lenses, and we inspect pictures

of naked young women.”

I mimed this activity, preparing to impersonate the distinctive

Flynt drawl.

“‘I love a hairy pussy’ is something I’ve heard Larry say far more

often than ‘lunch is on me.’”

Serious gamblers, in my experience, can’t get enough jokes that

demean a miserly multimillionaire. Against all odds, I was still

ahead. I put a hand on Larry’s shoulder, and he turned to me. His

green, yellow-rimmed eyes sized me up. His icy stare was the look

he’d give across a poker table, calling a bluff.

“The secret truth about Larry Flynt is that he is the most pussywhipped

man I have ever met. He talks a big game, but his wife Liz

only lets him wear the pants because it takes two grown men to lift

Larry off his ass so she can strip those pants off of him.”

I began to understand the emotions of the dive-bombing

kamikaze pilot. The end is near. It will be swift and spectacular.

“I’m just reporting the facts.

“Liz Flynt met Larry when she went to work for him as a private

nurse. She weaned him off of painkillers, turned his health around

and whipped him into shape. Then she persuaded him to marry her.

I always wondered how she did that.

“I discovered Liz’s secret one night recently when my wife and I

went out to dinner with the Flynts … Dutch treat.”

I’d been losing my audience, but again the penny-pinching reference

brought them to my side.

“Larry has a wandering eye. Every time any woman from any

table in the restaurant stands up to go anywhere, Larry’s head pivots,

and his eyes track her tits. I could see that this was pissing off

Liz, and I tried to warn Larry, but he never listens to me. Finally,

nurse Liz reaches into her purse and pulls out this giant enema

bag, right there in Wendy’s.

“So that’s Liz’s secret. The corrective enema.”

I prepared to soften the sarcasm by bringing the joke around so

that I too am a butt of it.

“The sad part about this story is that my wife made me stop on

the way home and buy one of those bags.”

If you consult the tape and listen closely, you will hear that this

stab at self-deprecation wins the affection of the crowd. They appreciate

that I am not mean-spirited. I see the humor in myself as well

as in those around me. Love inhabits that applause and laughter.

Video does not lie. But no love inhabits the face of Larry Flynt. He

recognizes my feeble stab at self-abnegation for the meaningless,

manipulative gesture it is. As far as he is concerned, I am finished.

“So I could talk all night about Larry’s philanthropy and generosity.

Because I’m a huge bullshitter.

“But it is time to discuss Larry’s professional achievements.

When the history is written, what will be seen as Larry Flynt’s defining

contribution to American culture?

“Will he be remembered for the battles for free speech and a

free press?”

“Yes!” responded an enthusiastic butt-kisser in the audience, as

if I’d been fishing for that answer.

“Or might Larry’s lasting fame be as the pornographer who

cared enough to save President Clinton’s ass?”

Again, rumbles of affirmation formed, but I snuffed them.

“Perhaps our grandchildren will recall our guest of honor as the

man who offered Jenna Bush $10 million to pose nude in Hustler

magazine. Plus a quart of Colt .45 if she spreads her butt cheeks.”

The crowd was thrown off. Had they really thought I was paying

serious tribute? There seems to be no end to the limits of human

miscommunication. My subtext, for instance, had been lost even on

myself. The underlying message was coming clear: I was tendering

one of the most passively aggressive resignations in history.

“My vote is that we remember Larry as the guy who invented the

Scratch ‘n’ Sniff centerfold, an innovation that was created in his

own image. The Scratch ‘n’ Sniff centerfold is the perfect representation

of Larry’s legacy. When you scrape its surface, it’s sort of

flaky, and it smells vaguely fishy.”

I was on a slide, falling flat. Now for the soft ending.

“Larry, thanks for all the excitement over the years. I’m grateful

for all the opportunities you’ve given me. Even this one. I really do

love you.”

The “love you” came out spontaneously. There’s no mention of

love in the 24-point type of my roast script. I took my seat, after

the feeblest attempt to shake Flynt’s hand, and the red in my face

deepened as I endured an embarrassment of applause. Finally,

Roger Clinton was called to the podium, and the attention shifted

to his slow-pitched softballs. I estimated how many weeks would

pass before I was Hustler history. That “really do love you” bit had

sealed it.

The word love doesn’t occur naturally in my everyday conversation.

The wife complains that she never hears it. To this day, I feel

a twinge of shame for having made the public avowal to my old

boss. Telling someone you love them in front of a crowd is seldom

the right thing to do. Take for example the LFP Christmas party of

1998: Doug the bodyguard rolled gold-plated Larry to the center of

the cleared dance floor, and the publisher addressed his guests and

his minions through a handheld microphone. Bob Livingston, the

freshly elected Speaker of the United States House of Representatives,

had announced his resignation that very day, claiming that

he had been “Flynted.”

Larry’s voice quavered, and his hands trembled as he recounted

LFP’s victories of the past year. He cited the company’s

unprecedented profit margins. The moment was perfect for

announcing year-end bonuses, something that had been missing

from our annual festivities since Larry’s emergence from a narcotic

stupor several years earlier. We employees held our collective

breath. Larry faltered; something had stuck in his throat. He girded

himself, and then forced out the four words that had gagged him:

“I love you all.”

Saying “I love you” cost him almost as much as if he had offered

to give us money. I had felt his pain and admired him for enduring

it. Still, not one of us employees wouldn’t have rather had a check.

In the story of Larry and me, love is clearly an overstatement, best

left unsaid.

Order online at Amazon