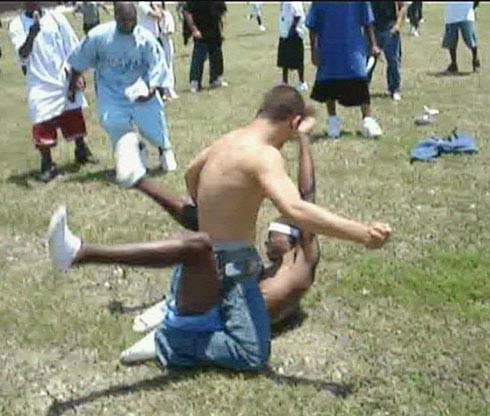

This is not a scene from the Brad Pitt movie Fight Club. Instead, it involves real teenagers in an underground video called Agg Townz Fights 2. Their ring: the grassy schoolyard of Seguin High School here. They’re engaged in a disturbing extreme sport that has popped up across the nation: teen fight clubs.

This year, authorities in Texas, New Jersey, Washington state and Alaska have discovered more than a half-dozen teen fight rings operating for fun — or profit. These illegal, violent, often bloody bouts pit boys and girls, some as young as 12, in hand-to-hand combat. Some ringleaders capture these staged fights with video or cellphone cameras, set them to rap music, then peddle homemade DVDs on the Internet. Other fight videos are posted on popular teen websites such as MySpace.com and YouTube.com.

Some bouts are more like bare-knuckle boxing matches, with the opponents shaking hands before and after they fight. Others are gang assaults out of ultra-violent films such as A Clockwork Orange, with packs of youths stomping helpless victims who clearly don’t want to fight.

"When you watch the video, you’re appalled by the savagery, the callousness, the lack of morality," says James Hawthorne, deputy police chief of Arlington’s West District, who’s leading a crackdown on fight clubs. "This is an indictment of us as a society. It’s not a race issue or a class issue. It’s a kids issue."

Many fight-club brawlers are suburban high school kids, not gang members or juvenile criminals. Chase Leavitt, son of U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Mike Leavitt, was arrested for participating in a fight club at a Mormon church gym in Salt Lake City in December 2001, when his father was Utah’s governor.

The younger Leavitt, then 18, pleaded guilty to disturbing the peace and trespassing in September 2002 and was sentenced to 40 hours of community service, says Sim Gill, the chief prosecutor of Salt Lake City who handled the case.

According to Gill, Chase Leavitt laced up boxing gloves and punched it out with a 17-year-old opponent at the church, which is in an affluent neighborhood. Organizers handed out fliers advertising the fight. About 100 students from Leavitt’s East High School paid admission before cops raided the premises. As the teens fled, they dropped a video camera with footage of several bouts that night.

"This is not something that just happens in poor neighborhoods," Gill says. "This crosses all socioeconomic bounds. It’s happening in middle-class and upper-middle-class environments."

Secretary Leavitt and Chase Leavitt declined to comment, referring calls to attorney Loren Weiss. He says Chase Leavitt was "prosecuted for who he was, not what he did."

Fight clubs tap into a dark, nihilistic "part of the American psyche fascinated by the spectacle of blood and violence," says Orin Starn, cultural anthropology professor at Duke University who teaches about sports in American society. "This does seem a phenomenon of the Mortal Kombat, violent video game generation. The fight club offers the chance to bring those fantasies of violence and danger to life — and maybe have your 15 minutes of fame in an underground video."

Chuck Palahniuk, author of the cult 1996 novel Fight Club that was the basis for the 1999 movie, declined an interview request but said, "God bless these kids. I hope they’re having a great time. I don’t think they’d be doing it if they weren’t having a great time."

Fights in public, in daylight

This middle-class community of 360,000 residents between Dallas and Fort Worth is the home of baseball’s Texas Rangers and the Six Flags Over Texas amusement park and the site of the Dallas Cowboys’ planned football stadium.

Sitting in his office on a hot Texas afternoon, Hawthorne shakes his head as he watches the two-hour Agg Townz 2 (slang for Arlington) video, featuring teens mostly from Arlington and the neighboring town of Mansfield punching, kicking and stomping each other.

Hawthorne points out that many fights on the tape take place in daylight on pleasant, tree-lined streets with brick homes and well-tended lawns. One fight turns into a mini-riot with dozens of teens rampaging through the parking lot of a McDonald’s restaurant. Another running brawl spills into a busy city street, where the fighters slam up against rolling cars.

In almost every fight, there are dozens of teens cheering on the pugilists or snapping pictures. Sometimes their schoolbooks are spread out on the lawns. In one scene, an adult holds the hands of a toddler who watches a fight as if it’s another street game. In another, teens watch the tape as entertainment at a party like a music video.

During the most gruesome footage, one falling fighter strikes his head on a sidewalk and is knocked unconscious. While the defenseless teen’s arms jerk spasmodically and his eyes stare upward, his opponent continues to belt him in the face. As the injured teen is dragged away, his head leaves a bloody smear on the curb.

Police here learned about fight clubs after Kevin Walker, 16, was jumped and kicked in the head outside his grandmother’s house March 11, suffering a brain hemorrhage and other injuries. Arlington police arrested the producer of the Agg Townz series, Arlington resident Michael G. Jackson, 18, and five of his friends, ages 14-19.

Hawthorne says the group would pay teens a few bucks to fight, or attack other youths, then film the violence with video or cellphone cameras. Jackson edited the footage, set it to rap and sold two volumes through his own website for $15-$20 each. The footage of the Walker attack (seized by cops as evidence and never released) was part of a third volume Jackson was working on when he was arrested, Hawthorne says.

On Thursday, Jackson and three other adult defendants were indicted for aggravated assault on Walker and engaging in organized criminal activity, both felonies, says Jennifer Tourje, assistant district attorney for Tarrant County. They face possible penalties of two years’ probation to 20 years in a state penitentiary if convicted of aggravated assault and five years’ probation to 99 years in prison if convicted of engaging in organized criminal activity. Both charges also carry possible fines of $10,000, she adds.

Hawthorne has asked the IRS and the state comptroller’s office to investigate whether Jackson paid taxes on his DVD sales. Several parents of injured teens are considering civil lawsuits against Jackson, Hawthorne adds.

In Arlington, fight-club participants can be arrested on several felony and misdemeanor charges, including aggravated assault, fighting in public, engaging in organized crime and criminal mischief. Texas law allows police to arrest active spectators as accomplices to fighting in public. As part of the crackdown that began May 10, cops have made 40 arrests, including Jackson and his friends, and issued about 200 citations involving fighting in public or watching arranged brawls, police spokeswoman Christy Gilfour says.

In an interview with USA TODAY, Jackson confirmed filming fights and selling DVDs of them. However, he denies instigating fights or paying teens to take part in them and says he has shut down his website. Jackson says he simply saw a financial opportunity to exploit fights that were happening anyway.

"I just used my business-savvy mind," says Jackson, who’s seen break dancing and flashing a wad of cash in the videos. He says he never participated in the fights, and he won’t say how much money he made or how many DVDs he sold.

His Dallas-based attorney, Ray Jackson (no relation), calls the organized crime charge "ludicrous" and predicts his filmmaking client will become another Spike Lee. The lawyer adds that although the Agg Townz series has become a "cult classic," his client has not made money from it. Most DVDs in circulation are bootlegs from which his client did not get a cut of the proceeds, Ray Jackson says.

"This was low-end equipment and high-end talent," the lawyer says. "That’s why it sold."

Messaging fuels combatants

Teen fight clubs have staged bouts on school campuses and in backyards, city streets, public parks, parking lots and gas stations.

Mac Bernd, superintendent of the Arlington Independent School District, says ringleaders have orchestrated fights the same way they do parties: through word-of-mouth, phone calls and text messages. Text-messaging enables instigators to inflame a minor dispute between teens at breakfast into a full-scale brawl by lunch. "You have an electronic rumor mill that moves at the speed of light," he says. That’s why Bernd, despite the objection of some parents, is outlawing all telecommunications devices for the 2006-07 school year — including cellphones, pagers, beepers, PDAs, digital and video cameras, MP3 and CD players and video games. The ban covers 74 schools with 63,000 students, including a half-dozen high schools with 20,000 students.

"We’ve concluded schools are for teaching and learning," he says.

Race does not appear to play much of a factor in teen fight clubs’ bouts. Rita Sibert, president of the Arlington chapter of the NAACP, says the clubs include "a mix of all children, all races."

Most of those in the Agg Townz video are African-American. However, just a week after Jackson’s arrest, Arlington police booked a group of 11 white teens and one Hispanic youth for fighting in public, Hawthorne says. A fight video made in nearby Grand Prairie shows mostly white teens, city police Detective John Brimmer says.

Silence surrounds participants

The fictional fight club led by Pitt’s character, Tyler Durden, in the 1999 movie was made up mostly of men in their twenties who made a sadistic and masochistic sport out of fighting one another.

Durden’s main rule for his club became the movie’s signature line and a slogan in popular culture: You do not talk about Fight Club.

Teen fight clubs in Arlington often and elsewhere follow that advice, and police and school authorities have been frustrated by the wall of silence that has surrounded the clubs. Not one of the hundreds of parents who viewed clips from Agg Townz 2 at several community and church meetings seemed to have a clue that fight clubs existed — or that their kids were involved, Hawthorne says. Among local teens, he says, the clubs have been common knowledge.

"It was a revelation for the parents," notes the NAACP’s Sibert.

Bernd and other school administrators say most teens, even the ones absorbing the bloodiest beatings, refuse to roll over on fight-club participants for fear of retaliation by ringleaders or gangs involved.

The teen beaten into bloody unconsciousness in the Arlington video has not come forward and is still unidentified, Hawthorne says. Grand Prairie police have made no arrests in their case because no one has filed a complaint, Brimmer says.

Citing such secrecy, Bernd says he suspects there are more fight clubs operating under the radar.

"It’s almost like the kids have created a completely different world we don’t have access to and don’t understand."